Kasteel Batavia

Kota Tua, Jakarta Old Town, Indonesian

I recently revisited Jakarta’s Kota Tua – the old city. During the nearly three-and-a-half centuries of the Dutch East India Company’s rule of the Indonesian archipelago, Jakarta was called Batavia. Officially known as VOC, the company led by its governor general, Jan Pieterszoon Coen, conquered the small town of Jayakarta in 1619. After taking over the place, the Dutch are said to have destroyed the urban settlement of the local sultan and built a new town by clearing the ruins of the old. They named it Batavia and made it the headquarters of their new expanding empire in Asia. From a little colonial outpost in the 1620s, over several centuries of developments, Batavia, the capital of the Dutch East Indies, became a vast city by the Twentieth Century.

However, when the Japanese invaded and captured the Dutch East Indies in 1942, they changed the name of Batavia back to Jayakarta. This act by the Japanese was said to be a clever strategy that won the hearts of Indonesian nationalists seeking independence from the Dutch. The Japanese also destroyed the large statue of Jan Pieterszoon Coen on 7 March 1943. He was known as the butcher of the Banda Islands, who caused a genocide there in 1621 to monopolise the trade in nutmegs. His statue stood in Lion Square, a centrally prominent location in Jakarta. After independence, the square was renamed Lapangan Banteng, where a new statue stands majestically in the centre of a designed public space with water and elevated seatings – called West Irian Liberation Monument that commemorates the incorporation in 1963 of the western half of Papuan Island into Indonesia’s territory. Incidentally, this was exactly thirty years before the day I first left Bangladesh with my family for London on 7 March 1973 from Dhaka on a British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) flight. I was only ten years old at the time.

Unlike in my previous visits, this time, I was prepared with some extra knowledge about the old city, how and when its journey began, and its expansion over four centuries. I also came up with a specific purpose: to familiarise myself with certain aspects of the old city and its sites and learn about some individuals and episodes associated with the earliest history of Jakarta, when the Dutch VOC was building their headquarters. On my previous visits, I enjoyed many things the old Jakarta offered. I looked at the Dutch architecture still standing and wondered about the Dutch city planning and the spaces they created – such as the Town Hall, Fathallah Square, buildings, canals, public transport and roadways. Moving around the old city made me wonder and reflect on what life might have been like in a bygone era. It made me imagine many scenarios, including exploring the similarities and differences between the Dutch Batavia (Jakarta) and British Calcutta (Kolkata) regarding how the Dutch and the British built these two cities from scratch and made them the respective capitals of two European Empires in Asia.

I took a bus to the old city from my hotel, which was not very far, and the bus route was the most convenient mode of transport from where I stayed. I could have also taken a train from a stop about ten minutes’ walk from my hotel, whose last stop in the northward direction is the station called Kota, which means city. People in Indonesia intuitively understand that Kota in major cities means the old city.

I got off the bus at a stop along the renovated left frontage (when facing northwards) of Ciliwung – a river and a vital waterway for the city and the regions as it is of the main channels that drain the waters of the nearby mountainous regions of West java in and around Bogor. After getting off the bus, I used my smartphone’s Google map and an old drawing to navigate myself to the site of the old Dutch fort called Kasteel Batavia. I read on the internet that a tiny section of the fort is still there as ruins, although most had disappeared a long ago, and no traces exist today.

The old town is very busy, and on weekends, it gets even busier, mostly with ordinary Indonesian families who come from all over the vast archipelago nation for entertainment, relaxation and to learn about the history of their capital city – or now as the premier city because it is no longer the capital. The new capital of Indonesia, called Nusantara, was moved to the island of Kalimantan in 2024. In addition to the Jakarta History Museum, several other museums and offers cater to many kinds of people and what they are looking for – to participate in various activities, enjoy the entertainment and relish the street food galore.

I will write more about other places I visited in old Jakarta and my experiences with the Jakarta History Museum and walking around Fathallah Square. But here, in the following sections, I will briefly share my search for and how I found the last remaining bits of the Kasteel Batavia. After getting off the bus, I crossed the river using one of the overbridges and walked through a narrow road straight to Fathallah Square. It was uncharacteristically quiet, most likely due to the drizzling raindrops and signs of an earlier deluge everywhere. While walking, I took many photos of whatever caught my fancy. I read in a book that walking northwards from the square in Jalan Cengkeh (Clove Road) takes you straight to the location of the ruins of the old Dutch fort.

So, I ventured north on the left side of Jalan Cengkeh, and soon, a man stopped me, who introduced himself as a tour guide and offered his services. I politely declined and told him that I was walking to find the remaining ruins of the old Dutch fort. He said, ‘Follow me’, and I walked with him on his right for about ten minutes when he stopped. He then showed me the directions to the fort and told me that after the railway bridge, I should turn right and keep walking, and I would soon see the fort. I did just that, but I didn’t expect what happened to my feet as the path was mostly filled with water and mud, and wearing a leather sandal made walking more difficult. I had to stop, buy a small water bottle to drink and request permission from the store owner to use water from a container outside the shop to wash the mud off my feet and sandals.

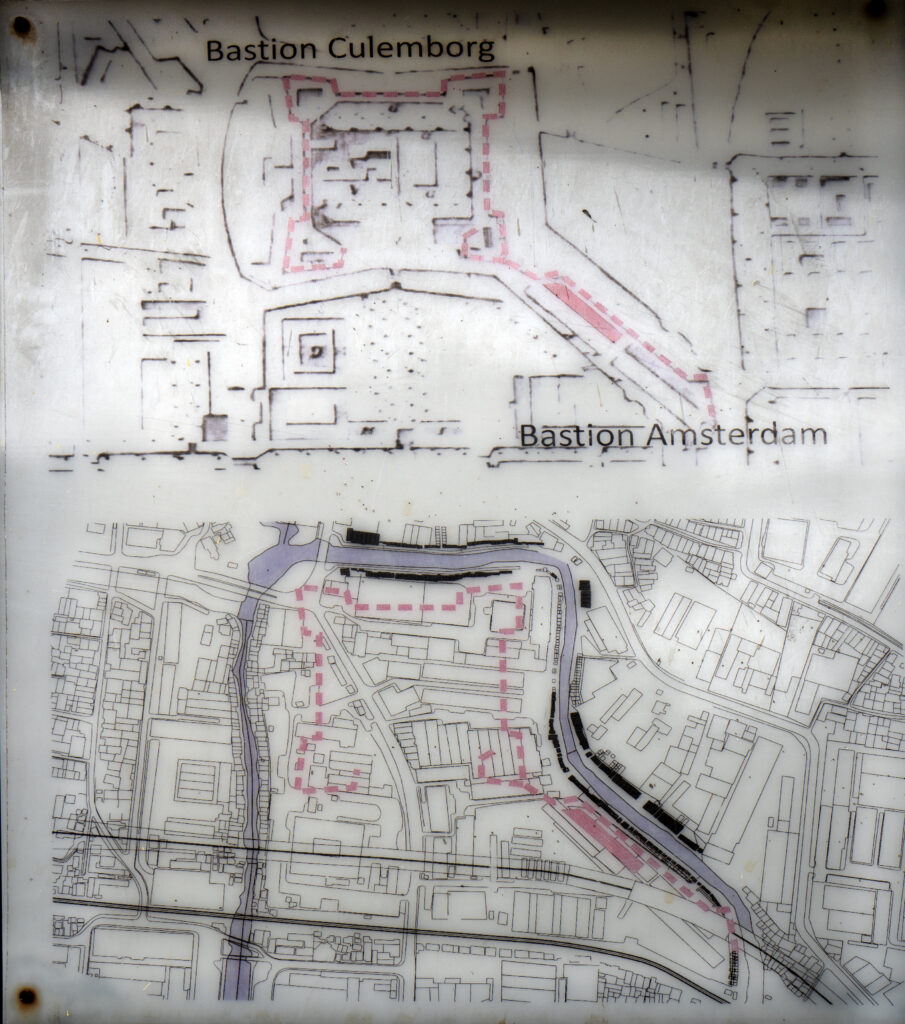

After walking for several minutes, I saw an old, damaged building and took photographs of the ruins from every angle. I was disappointed, however, as what existed was in a bad state. Further, although it was a two-story building – quite a large one – it didn’t look to be a part of the fort or be located within the fort perimeter. I looked at an old map located on the side of a section of a wall still standing although in pretty bad condition, indicating where the fort was.

Based on my investigation, the building I saw in ruins looked as if it was located just outside the main walls of Kasteel Batavia when they first constructed the latter. I need to look at the whole thing again with more focus to know the exact boundary wall of the original fort built in the early 17th Century and whether the wall perimeter included the building in ruins. If not, it must have been an addition to the Kasteel Batavia built sometime later. From the drawing below, taken from the information on the wall still standing on one side of the building, it looks like this ruin is located in the same place as the pink rectangular block below to the bottom right. If so, then it means this was not within the original boundary of the Kasteel Batavia but was built later in some lands just south of it.

As the weather was turning for the unpleasant and heavier rain seemed imminent, I left the area without exploring much of the surroundings of Kasteel Batavia. However, regardless of whether the old ruins were within the walls of Kasteel Batavia or outside, leaving the area quite early meant I didn’t get to know what the rest of the area, where the Dutch fort or castle was situated, looked like now. After a few days, I decided to go back and look around. This was a wise decision. After passing the ruins I had visited a few days earlier and taking more photos, I walked towards the east to get to the river and then along the river towards the northwest. When I entered the riverfront, I saw an amazing gem of gems. I will leave some photographs for you to imagine and not try to describe or explain what I saw and how I felt seeing what I saw. Rivers and canals provided extra defences against enemy attacks on forts, so most Dutch forts in Indonesia were surrounded by waterways.

This is a very short blog article; I will write a longer, more detailed piece later.